The Dartmouth Conference: A Pivotal Moment in AI History

In the summer of 1956, a group of visionary young men convened at a serene college campus in New England, United States. While others sought the thrills of outdoor adventures, these pioneers were set to embark on a groundbreaking experiment that would ignite decades of debate and fundamentally alter the trajectory of technology and humanity itself.

Enter the Dartmouth Conference—widely regarded as the birthplace of artificial intelligence (AI) as we understand it today.

What unfolded during those eight weeks would ultimately lead to the creation of advanced AI tools, including ChatGPT, and innovations that assist in diagnostic medicine, fraud detection, music curation, and content creation. However, this pioneering spirit also opened the door to complex challenges that the field continues to face. By reflecting on this monumental event, we might uncover pathways to a more productive future.

A Revolutionary Summer

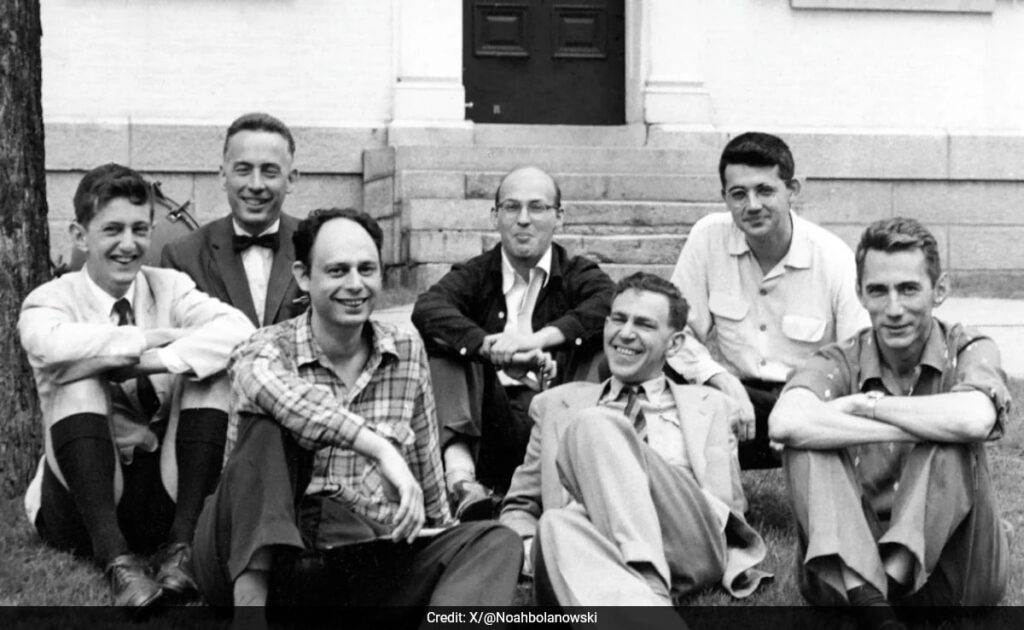

As rock ‘n’ roll swept through the mid-1950s with hits like Elvis’s "Heartbreak Hotel," and young people embraced James Dean’s rebellious aura, a different kind of revolution was brewing in a quiet corner of New Hampshire. The Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence officially kicked off on June 18, bringing together a unique assemblage of some of the brightest minds in computer science, mathematics, and cognitive psychology.

The brainchild of four eminent computer scientists—John McCarthy, Marvin Minsky, Nathaniel Rochester, and Claude Shannon—the conference attracted 47 participants who aimed to tackle a daring challenge: the creation of intelligent machines. McCarthy succinctly summarized their ambitious goal in the initial proposal, seeking to understand “how to make machines use language, form abstractions and concepts, solve kinds of problems now reserved for humans.”

Birth of a Field

More than just coining the term “artificial intelligence,” the Dartmouth Conference catalyzed an entire discipline of study. It marked a significant moment akin to a Big Bang in the realm of AI, laying the groundwork for concepts such as machine learning, neural networks, and deep learning.

Despite its legacy, the naming of the field was fraught with contention. Shannon preferred “automata studies,” while conference participants Allen Newell and Herbert Simon favored “complex information processing” for years to come. However, the adoption of “artificial intelligence” has since become a double-edged sword, fostering comparisons between AI and human intelligence that have had both positive and negative ramifications.

On one hand, this comparison has driven the development of AI systems that can exceed human performance in specific tasks, like beating champions in games such as chess and Go, or achieving remarkable accuracy in medical diagnostics. Conversely, this continuous juxtaposition has resulted in misconceptions, leading to exaggerated claims about machine capabilities. A program like AlphaGo may excel at its game, but it doesn’t possess the ability to write poetry, just as a sophisticated language model like ChatGPT is not sentient.

Overconfidence in AI Development

The optimism of the Dartmouth scientists was palpable, each convinced that they could crack the code of machine intelligence within that single summer. This overconfidence has been a recurring motif in AI’s historical narrative, often spurring cycles of enthusiasm and subsequent letdowns. Simon predicted in 1965 that machines would be capable of performing any human task within 20 years, while Minsky expressed in 1967 that the core problem of creating artificial intelligence would largely be resolved within a generation. In modern times, futurists like Ray Kurzweil project that we’re just five years away from AI matching human intelligence.

Rethinking Our Approach to AI

As we move forward in developing and implementing AI technologies, it is crucial for researchers, industry stakeholders, governments, and the general public to cultivate a more balanced perspective on AI.

An essential step is to embrace the distinct capabilities and potential of current machine systems, transitioning focus from the pursuit of “artificial general intelligence” to recognizing the unique strengths AI can offer—such as the impressive creative abilities found in generative models.

Reframing the dialogue from a competitive stance to one of collaboration is equally important. Rather than positioning machines against humans, we should explore how AI can augment human capabilities and foster creativity.

Moreover, ethical considerations must take center stage. Unlike the Dartmouth attendees, who largely overlooked these implications, today’s understanding of AI’s potential requires that we prioritize its ethical dimensions.

It is also vital to redirect research efforts toward AI interpretability, robustness, and interdisciplinary studies, while exploring alternative models of intelligence that don’t merely emulate human thought.

Lastly, we must temper expectations of AI’s progress. While enthusiasm for AI’s possibilities is warranted, a realistic outlook will help prevent the cyclical disappointments of the past.

Reflecting on the legacy of the Dartmouth Conference—68 years after that transformative summer—it is a moment to celebrate the ambition and foresight of its participants. Their pioneering work has laid the foundation for the AI revolution we witness today.

By shifting our approach to prioritize utility, collaboration, ethics, and measured expectations, we can honor the visionary spirit of the Dartmouth Conference and chart a beneficial course for the future of artificial intelligence. Ultimately, true intelligence lies not just in technology but in our wisdom in utilizing and developing these powerful tools.